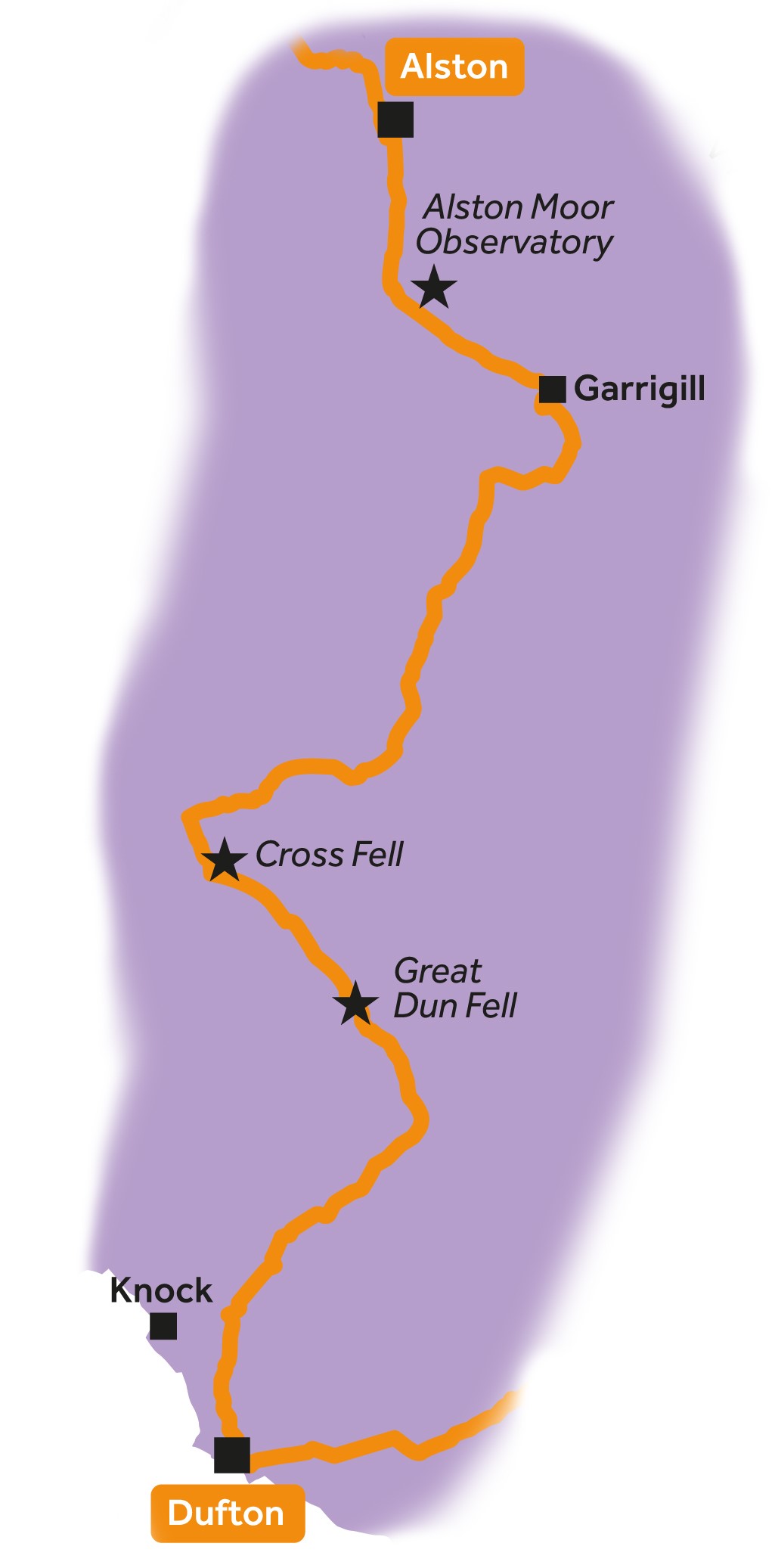

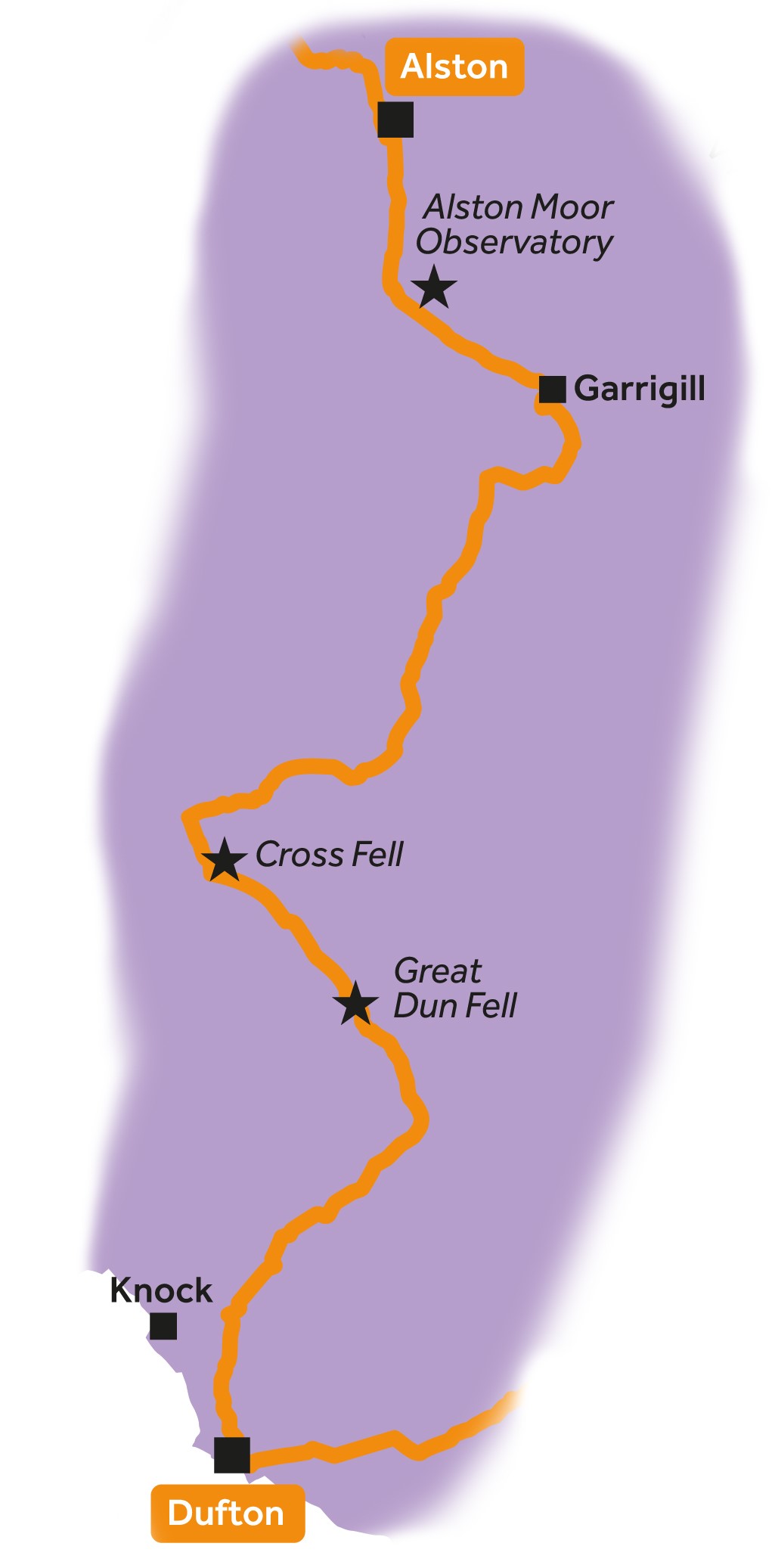

Leg 2Dufton to Alston

Leg 2 of the multi-day Roof of England Walk – a journey around the North Pennines. The longest day on the route traverses the trio of Great Dun Fell, Little Dun Fell and Cross Fell. The tough climbs are rewarded with panoramic views. Linear route – 31km.